Zoriana – Patterns of Identity

The vyshyvanka (embroidered shirt) accompanied Zoriana through one of the most difficult moments of her life – during evacuation. Because of the war, she had to leave behind her home, her city, and her loved ones. Long before February 24, 2022 – like many other women – Zoriana had an emergency bag ready: documents, water, food. And something more: two embroidered shirts.

It wasn’t just another item in her bag – it was something meaningful. Whenever she reached for her passport or a bottle of water on the road to Poland, one thought kept running through her mind:

Just don’t lose the vyshyvanka.

Zoriana clearly remembers the embroidered shirt her mother wore when she was a child. Her mother learned to embroider as an adult. She had lost her own mother – Zoriana’s grandmother – when she was just three years old, and was raised by her father and older sister. Neither of them had a talent for needlework. It was her mother who picked it up. She first made a vyshyvanka for herself. Then one for her daughter—Zoriana. Now, she’s working on one for her granddaughter.

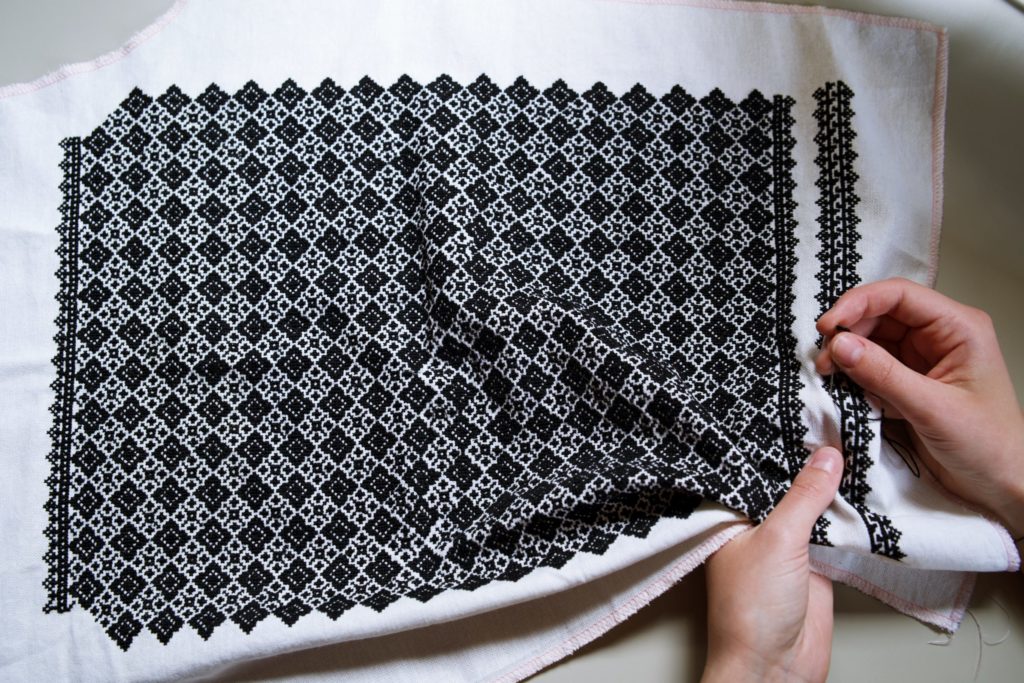

The Borshchiv Vyshyvanka

The shirt Zoriana took from Ukraine in her evacuation backpack is a Borshchiv vyshyvanka—a traditional design from the Borshchiv region. Dense as a forest, embroidered with thread on linen fabric. It’s a bit scratchy, but that’s how it’s meant to be – real. Not for tourists. For oneself. She and her mother made it together over the course of more than a year and a half. They chose the threads, adjusted the colors, refined the details to match Zoriana’s personality. It wasn’t just a pattern, it was something like a self-portrait or a fingerprint.

This is my vyshyvanka. Different from all the others. Because I made it with my mom, with her hands. But it speaks about me and who I am.

Vyshyvankas are made from cut-out fabric pieces that are embroidered separately—the sleeves, the front, the back. Then a seamstress puts them together. This method ensures the embroidery is placed precisely where it should be.

When Zoriana and her daughter left Ukraine, they didn’t know where they were going. First, they ended up in a village near Lviv. Then, with the help of friends who picked them up at the border, they traveled to Biłgoraj, Poland. She knew she couldn’t wait—she looked for work. In Warsaw, she found her way to the PCPM Foundation. She still works there today.

But through all the chaos and uncertainty, the vyshyvanka stayed with her.

Whenever I had to take something out—documents, water, something for my daughter—I always checked if the shirt was still there. If it was, I knew everything was okay.

Eventually, she hung it in the wardrobe of her new apartment. And she started wearing it—to work sometimes. Without any special occasion. Just on days when she wanted to feel more like herself.

Her daughter’s vyshyvanka also fit into Zoriana’s backpack. When Ania outgrew it, they gave it to a Polish friend, a girl from Warsaw, who now happily wears it to school. Now a new vyshyvanka is being made for Ania—black linen, entirely embroidered on the sleeves.

Ania chose the pattern herself. That’s very important—it should be decided by the person who will wear it. It has to be simple, without extra embellishments. Just the way she wants it.

Zoriana doesn’t forget about Vyshyvanka Day—celebrated in Ukraine for many years now, on the third Thursday of May. In Poland, she reminds her friends in a group message:

Girls, don’t forget—we’re wearing them tomorrow!

World Refugee Day – June 20 – is a reminder of the millions of people who are forced every day to leave their homes, their countries, their “normal lives.” But what often goes unnoticed in public discourse is the fact that people don’t leave everything behind. They carry something deeply personal – their identity. We want to highlight that. That’s why we’re publishing “Patterns of Identity” – stories about what refugees truly carry with them. From Ukrainian vyshyvankas and gerdans, to Palestinian tatreez, to Sudanese, Ethiopian, and Kenyan fabrics, jewelry, and handicrafts. Each of these patterns is more than just aesthetics—they are presence and memory. More patterns coming soon.