I’m making myself plans A, B, C… all the way to the end of the alphabet. But it’s worth it.

The SENSUM Addiction Treatment Center in Pszczyna is the only facility in Poland offering inpatient addiction treatment in Ukrainian language. In Poland in 2024, 31,042 people were experiencing homelessness. About 6% of them were from Ukraine. Migration, loss of property, trauma, and lack of housing security are factors that increase the risk.

Alcohol destroyed all my relationships

Serhii was brought to the center by a friend. He only intended to detox after an alcoholic bender so he could return to work at the construction site the next day. Once there, he learned about the possibility of inpatient treatment and about the option of receiving financial support for his stay from the PCPM Foundation.

“Honestly, in those last days before admission I couldn’t cope anymore. I didn’t know what to do. My wife left me, I broke down and just gave up. I hit rock bottom; I had nothing left to lose. Drinking destroyed all my relationships — because what kind of relationships can you have with someone who behaved the way I did? I even lost touch with my eldest son, because he had had enough of it all,” Serhii tells us during our meeting.

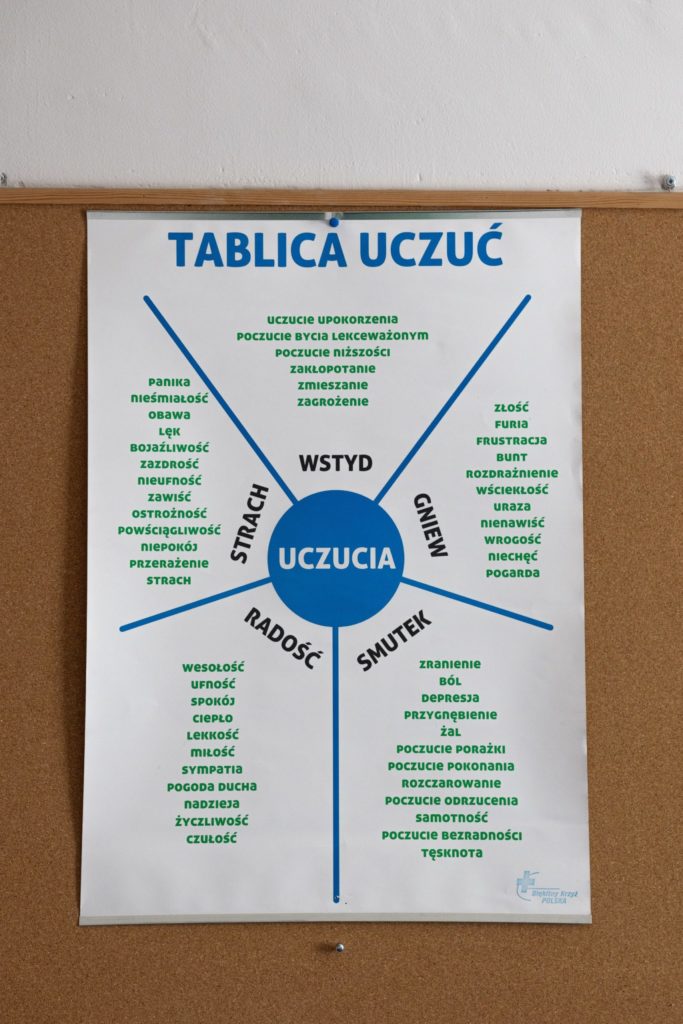

A day at the Pszczyna addiction treatment center starts with breakfast at 7:30, by which time patients must have completed their morning routine. Around eight o’clock, they go to structured group therapy sessions. These begin with what’s called the “pulse” — therapist listens to what the patients are coming with that day. Then there is a micro-education session, with content tailored to the patients’ current struggles. At 2:00 p.m., there is lunch, followed by free time. In the evening, usually before or just after dinner, there is another group session to close the day and process emotions. Topics include mindfulness training, understanding disorders, and neuropsychology — both theory and practice.

I didn’t know treatment could look like this. I sobered up here.

“Everything was new to me,” says Serhii. “I didn’t know such a place existed, that treatment could look like this, and that patients could be treated with kindness and respect. I sobered up here, I became calmer, and now it’s easier for me. At first, you bottle everything up. Then it hits you that you’re not alone, that others are going through the same, or even worse. And when you start letting it out, things slowly begin to sort themselves out in your head,” the man confides.

In addition to group therapy, each patient has an individual therapeutic program. Twice a week they meet one-on-one with their therapist.

“There’s a therapist here, also Ukrainian. I talk with her a lot, I have individual sessions with her. I can call her anytime. After I leave the center, I want to continue therapy. She told me that once a week a therapy group meets in Pszczyna, she’s yet to give me the details,” explains Serhii.

“Sometimes it feels like everything is going well and things are easy, but then you leave and the very difficulties that made you drink come back. I want everything I’m learning here to truly sink in. To take responsibility and not think that I’ll just have a drink, forget, and it’ll all go away — that’s the most important thing. I’m getting better at dealing with difficulties,” he adds.

Serhii has two sons — a 20-year-old who already has his own family, and a 5-year-old. They give him strength in his fight against addiction.

“When you drink, your mind changes. You spiral, and stupid thoughts come into your head. I’ve gotten rid of those here. Everything I could, I have thought through. Now I just need to clear my head and everything will be fine. I simply have to, because I have people to live for. And drinking is not living,” says Serhii.

Everyone experiences suffering

“A Ukrainian patient is no different from a Polish one. Both experience suffering. Addiction is a response to difficulties in resolving inner conflicts. Either the person lacks coping skills, or has too many problems weighing them down,” says Dorota Wojnar, director of the SENSUM Addiction Treatment Center in Pszczyna.

For someone with addiction, war is another hurdle and another trauma. But psychiatrist and therapist Roman Wojnar points out that the war in Ukraine actually reduced substance abuse. Based on his observations and research on the topic, people mobilize themselves, and the so-called survival mode reduces the use of psychoactive substances.

“We have to mobilize, it’s not the time for drinking,” he says. “The same thing happened in Poland during martial law — alcohol consumption and alcohol-related diseases dropped significantly,” the therapist adds.

Where do addictions come from?

“Addiction is a blameless, chronic, progressive, and fatal disease,” emphasizes Dorota Wojnar. “There are many concepts of how addiction develops.”

She explains: “A person, through socialization and bonding with an attachment figure — mother, father, caregiver — shapes appropriate emotional responses. The child is cared for, but sometimes has to wait. For psychological resilience to grow, the child must experience different emotions, including unpleasant ones like frustration, but must still feel loved and safe. If it is not the case — if a child is abandoned, or if sometimes the mother hugs and sometimes not — an ambivalent, destructive attachment style forms. The child doesn’t know if it’s good or bad. This leads to lifelong problems. In the brain, neuronal pathways form that provide calm and self-control. Harmony between the subcortical and cortical systems develops.

If this is missing, the adult can’t cope when things don’t go their way, and they suffer. And when they suffer, they look for relief. Eventually they discover cigarettes, alcohol. Each portion of alcohol, while destroying brain cells, also creates dependence. At first, alcohol acts as an anesthetic, a helper, a servant that shows up at the right time. But after a while, it takes control, and the person becomes enslaved. The brain craves it so strongly that eventually the only relief is a brief absence of suffering.”

All my fears and traumas resurfaced

“I’m here for a month. I was offered seven weeks, but I can’t take that much time off work. My boss doesn’t know I’m here. Anyway, I need to change jobs and my environment. I’m a bar manager, and there’s, you know, alcohol there. Guests come to drink, I have to pour, talk to them…” says Anastasiia, a SENSUM patient in Pszczyna.

“Outside of work, I have no interests or hobbies, no free time. I come home late at night and have just one day off a week. That day I do errands and spend time with my child. We go to the park, to the pool, see family. My child is now on vacation in Ukraine,” she says.

“I struggle with mixed addictions, but mostly alcohol. For a long time I used drugs, smoked, and drank, mainly due to my mental state. I reached a point where I couldn’t stop on my own and get back on track. That’s why I’m here. Of my own will. Substances were always in my life. I tried to fight addiction on my own, and there were long periods when I didn’t use. But if I wasn’t using hard drugs, I smoked more marijuana; if I wasn’t smoking marijuana, I drank more alcohol. Substitution. Sometimes I used everything at once. But I always functioned well, never lost my head,” says Anastasiia.

“Natalia, our Ukrainian therapist, pointed out that in Ukraine people often think: you’re only an addict if you need detox; if you don’t, you’re healthy. The differences in approach are big,” says therapist Roman Wojnar.

I wanted to run away

“Detox takes place on the ground floor,” explains Dorota Wojnar. “Several people are involved. Withdrawal syndrome is always an existential crisis to some degree. When patients lose something, they feel anxiety, this often triggers fears. Withdrawal symptoms can be so strong that there’s fear of death. At this stage, patients are given medication and have someone available for support from the start. They’re not alone. Once the alcohol is fully flushed out, we start psychoeducation. Then comes the first individual session.”

“At first it was very hard for me here — both mentally and physically,” admits Anastasiia. “All my fears and traumas resurfaced. It was hard to be away from my fiancé. One night I got up and wanted to run away. The only thing that stopped me was pouring rain. I just went outside, smoked a cigarette, and decided to wait until morning, because then we have breakfast and immediately go to group therapy. There are people there who are going through the same as me. They supported me a lot. I told them about my feelings, about what hurt me, and I felt a little lighter. ‘We won’t let you go, stay, you can’t give up, we understand you,’ they said. Everyone here really cares for each other. If someone is missing, they ask why, if they told anyone, if they called… if they even got up.”

People of all ages and with all kinds of problems come to Pszczyna. Some only come for detox and don’t think they have an alcohol problem. They detox their bodies and return to their lives. Others come because they’ve lost their sense of purpose and don’t know what to do next.

“Like me,” says Anastasiia. “But now I feel good. I am able to say: ‘Hello, my name is Anastasiia, I’m 35, I’m a drug addict and an alcoholic.’ It became normal for me. I accepted myself, realized I have a problem, and I hope they’ll help me here. After that, somehow things will work out. I know the day will come when I leave this center and face the choice: return to the life I used to know, or start a new one. I’m making plans A, B, C, D… all the way to the end of the alphabet. I don’t know what my life will look like, I can’t see it yet. But I will look at everything with sober eyes, controlling my emotions,” she confides.

Where can you get support?

“Our generation didn’t go to psychologists. Now I think, if I had taken that step earlier, everything would have turned out differently,” says Serhii.

If you are from Ukraine, struggling with addiction, at risk of homelessness, and want to undergo inpatient alcohol treatment, visit the PCPM Foundation website and fill out the form. As part of the Prevention of UA Refugees’ Homelessness in Poland Project, funded by the Citi Foundation, the PCPM Foundation has planned a range of activities to help refugees from Ukraine who are experiencing homelessness find support.